The dominant reaction to the election of a new pope has to be wonder. It may be colored by any number of other impressions depending upon the person reacting and the individual chosen. It may be tinged with various shades of joy, optimism, hope, concern, and even, in some cases, dread. But the thing about this faith--the absolutely impossible thing--is that almost two millennia after Peter asked the Lord, "Quo vadis?,"1 and then turned around to meet his death, we have, by one means or another, been passing along the keys to the kingdom of heaven to the next successor. Every generation raises up new men to take the role: saints, cads, placeholders: all manner of men.

Everyone believes they live in deeply consequential times. Sometimes it's even true. In our time, the faith has been marked by the Second Vatican Council and its implementation, which can be divided into three general periods.

There was the initial silly season of liturgical collapse and doctrinal revolt: a Protestantizing, liberalizing attempt to deface the faith. The collapse was, gradually and incompletely, addressed by a long period marked by the dual pontificates of Pope St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, which attempted to check that decline, consolidate the conciliar goals into something recognizably and functionally Catholic, and rebuild the faith into what Ratzinger called an affirmative orthodoxy: the "yes" to God that was involved in taking doctrine and dogma and liturgy seriously as it spoke to new realities.

The last period was the Francis pontificate, which saw a retreat from many of the priorities of his two predecessors. It's very hard to evaluate Francis. The everyday rank-and-file faithful--the majority of Catholics--have one view of him, and it tends to be positive. They aren't immersed in day-to-day news from the Vatican, don't read encyclicals, and are often unaware of the controversies that agitate Church observers and commentators.

To them, Francis was the pope, and their inclination was—as it should be—to view him in the best light. If some story was circulating in the media about something he said, they mostly took it in stride and moved on to getting the kids ready for school or cooking dinner. They didn't dwell on it, and they didn't need to. He was the pope.

And so he was often an inspirational figure for many. This is right and good. I would no more tell parishioners who expressed great love and respect for the Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church that they were wrong to do so than I would insult their mother.

On the other hand, the very-involved, high-information, heavily-online faithful divided into several mutually antagonistic streams: the Popesplainers, for whom he could do no wrong; the Trads, for whom he could do no right; and the Company Men, who liked some things, disliked others, but generally thought either idolatry or abuse of the Supreme Pontiff was bad.

As I wrote elsewhere, there was good and bad in this papacy. I believe his emphasis on the poor and call to the margins was very Franciscan and a worthy thing. I also believe his suppression of the Extraordinary Form of the mass was misguided and cruel. Following the diamond-like clarity of his immediate predecessor, he seemed to have an uncanny ability for confusing people. "Make a mess," is fine advice for a child splashing in puddles on a rainy day, but from a leader responsible for preserving and passing on doctrine, it's not the best.

Then there is the deeper problem, the one the church can't seem to escape. Running through every papacy for the past three decades was a river of filth that did grave damage to the church. Of the three men who occupied the chair of Peter, Benedict took the abuse scandals the most seriously, and still failed; John Paul refused to believe it and his failures should have at least delayed his canonization; and Francis left a mixed legacy, both creating new ways of addressing abuse and actively protecting abusers. After all this time and these revelations, it appears as if we've learned nothing at all.

I was not alone in these conflicted responses, but in the end, Francis left us with the church we have right now, in this moment in time, with a legacy of good and bad. It's worth trying to sort the good from the bad, but the ongoing attacks on the late pope serve no purpose. He's facing a Judge more true than you or me, whose winnowing fork will sort wheat from chaff. I trust that the Lord in His mercy will see him into heaven in His own time, and beyond that all I can offer is a prayer for his soul.

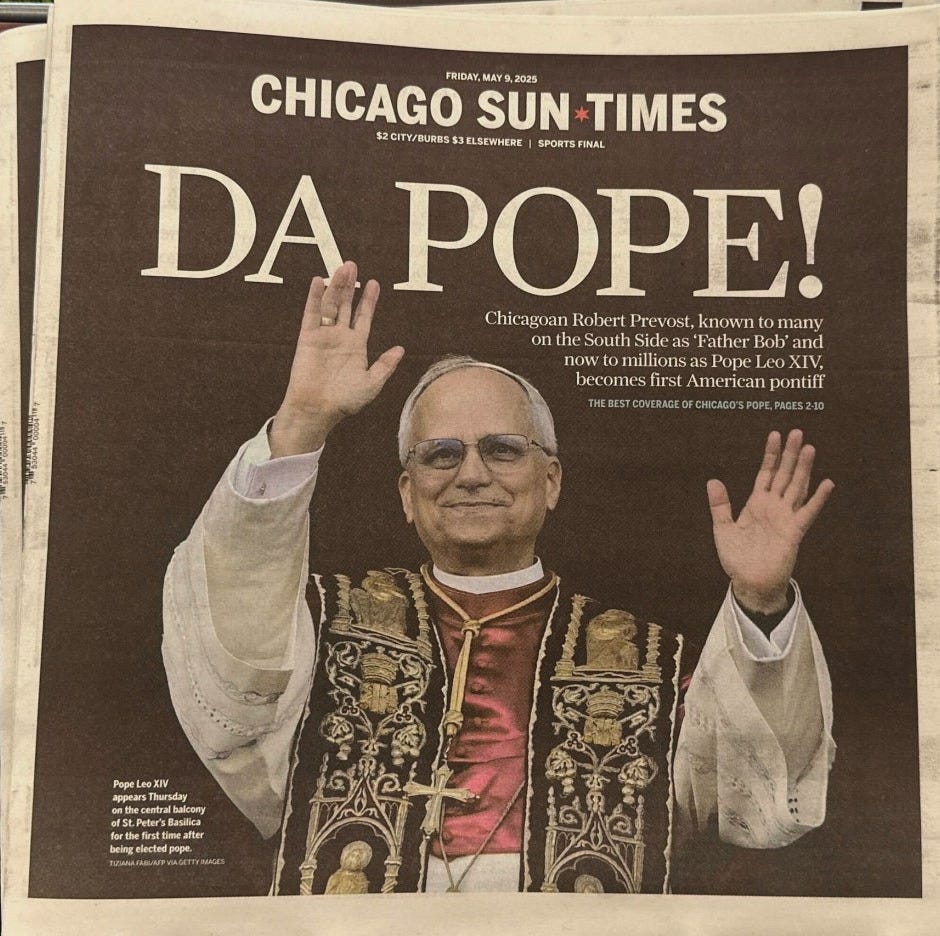

All of this is preamble (and probably too much of it) to the important part: where we go from here. Leo XIV has made a wonderful first impression: appearing on the balcony in the mozzetta; speaking Latin, Spanish, and Italian fluently; his deep immersion in Augustine; choosing to set himself in a line that stretches from Leo the Great to the prolific, brilliant, and holy Leo XIII; and all his words for the first few days. He has a reputation for being agreeable, even-tempered, and a good leader. The various "factions," to use an unfortunate word, largely appear to have embraced him. He seems to be a calming figure, and we really need that.

There's a danger, of course, that coming out these last chaotic years, Leo is functioning as a mirror, reflecting back our own desires. We're able to project our hopes onto him because he is an unknown quantity at this time. It's a good feeling to have, and there’s nothing wrong with it. Hope is a virtue. Submission to the Roman Pontiff is a requirement. Charity is an absolute demand.

A great deal is being either presumed about his priorities or spun into elaborate scenarios based on his words so far and his choice of regnal name. I don't think it's unreasonable to imagine him addressing technology as Leo XIII addressed industrialization. Beyond that, I'm not sure I can say anything more that doesn't amount to "I like the cut of his jib and hope for the best!" As opinions go, that's barely worth the time it takes to type it.

But hope is good. It is beautiful, in fact: one of the most beautiful things Christianity offers. We take it for granted, but there are religions without genuine hope. I recall a Buddhist teacher saying hope was bad because it prevents people from living in the now.

That's all wrong. Hope is memory and faith plus time. Hope is what draws us into the future, assured by the promises of Christ that something wonderful awaits even in the shadow of the cross.

And right now, I choose to hope for a papacy that will revitalize the faith in the ways God wants. They may not always be the way I want, but what do I know? I'm not the church's protector. I'm the least of her servants: a deacon, here to bind the wounds and teach the flock. The church has caused some of those wounds, and will again. The teaching has become harder because the world has become colder, but people are wearying of that cold and need the warmth of the church even if they haven't realized it yet. There's work to be done, and I've been assigned a small patch of believers to keep and to tend. The rest I leave up to the Holy Spirit, and offer a prayer for His new Vicar.

You bring up the majority of Catholics who see popes come & go with a docile, "he's our Pope. It's all as it should be." I felt a sudden longing to be like them. So much I can't do anything about & why bother knowing anyway? Popes do come & go. And we talk of Michelangelo.

(Anyway, just venting a sudden passion. Thanks for reading this.)

Give it time, there will be much for the papal posse and EWTN faithful to criticize. A couple quick examples: there are his tweets, rightly criticizing JD Vance, for instance. For another, his drawing reference to Rerum Novarum for his choice of name.

He may well be polite and "not confusing", but there will be feigned confusion all over the place if he starts talking much about the poor or migrants, or much about Catholic social teaching. He needn't address the extraordinary form, at all. God has given us what we need, just like with the previous Popes.