We are all Thomas

A homily for the 2nd Sunday of Easter on doubt, Francis, mercy, and a moment of the Spirit that is calling to all of us

My apologies if email subscribers are getting this twice. I accidentally posted it to Weird Catholic. Mea culpa.

This week’s homily had to do a lot: comment on the readings, mention the Easter vigil, acknowledge Divine Mercy Sunday, address the death of Pope Francis for mourning parishioners, and do it in about six minutes. Here are the readings.

Last weekend, we experienced a particularly joyful Easter, welcoming 16 new catholics into the church. And then on Monday, we awoke to a death in the family with the loss of Pope Francis. On his last easter, although he was sick, he went out to greet the faithful, who were so happy to see him. A few hours later, he was gone.

And it’s that mixture of joy and sorrow that really defines our faith, and which is displayed in our readings today.

The apostles are in fear, and Jesus offers them peace. And he gives them not just peace, but equips them with the power we hear about in the first reading. They work signs and wonders, and even the shadow of St. Peter performs miracles when it falls upon people by the side of the road.

But Thomas is not there when Our Lord comes to them. He does not see, and so he does not believe. That’s why history remembers him as Thomas the Doubter, but that’s not fair. If Peter or Andrew or James had been away on that first Easter Sunday, they probably would have doubted, too.

And Thomas was better than his doubt, just like we are better than our worst moments. Thomas is, in fact, all of us in four particular ways:

his courage

his curiosity

his doubt

his faith.

Thomas is mentioned in all four gospels, but he only speaks in John, and only says four things.

The first is when some of the apostles warn Jesus not to go to Judea because the people there will stone him. It’s Thomas who steps up and says, “Let us go, and die with him.” Those are the first words he speaks. As far as bravery goes, none of the others can match him.

And then, at the last supper, Jesus says he is going to prepare a place for them and then return to show them the way. Thomas doesn’t understand, and I wouldn’t have understood either. So like a good disciple, he ask a question. “Master we do not know where you are going, how can we know the way?” And Jesus says, “I am the way the truth and the life.” That’s a good student, trying to learn.

And then, of course, we come to Easter Sunday. Thomas is not with them when the Lord visits, and so he does not believe his friends. He should have trusted them. He should have trusted the Lord. But he’s like the Thomas speaking to you now: weak, unsure, needing to see in order to believe.

We shouldn’t fear doubt. Pope Francis himself has said that doubt can be a step towards a deeper faith. We all have a place of doubt in us, sometimes larger, sometimes smaller, and if we pretend we don’t, that can damage our faith. When we suffer, or witness evil, or are simply puzzled by the world, we can think of God and wonder “Are you even there?”

If we ignore or deny those thoughts, they can damage faith over time. So acknowledge your doubt, examine it, bring it before the Lord in prayer. God understands, and if you pay close attention, you may be surprised at how He provides an answer.

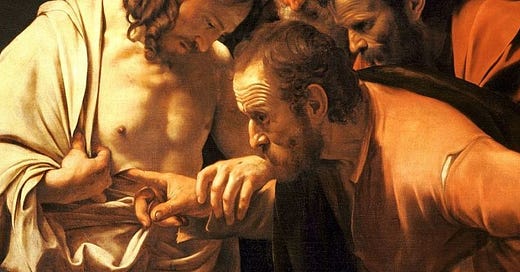

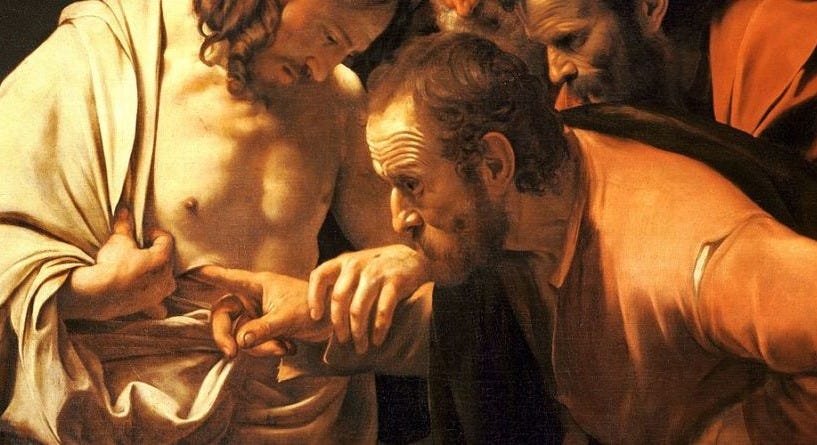

Jesus gives Thomas a week with his doubt. He returns the following Sunday–today–and offers his wounds to Thomas. I always imagine Thomas falling to his knees in shame, but the gospel doesn’t say that. Instead, we have his marvelous double declaration of faith. “My Lord and my God.” This is more than even the others offered, because he’s not just acknowledging the Lordship of Jesus: but his divinity.

And so he’s all of us: sometimes bold, sometimes questioning, sometimes doubting, and sometimes full of faith.

Thomas wanted to see the wounds of Jesus. Why the wounds. Why not see his face or hear his voice? Why does he want to touch the places where his Lord was pierced?

I think he knew the wounds of Jesus were important in ways he didn’t fully understand–that it was by these wounds we are healed.

In a homily about Thomas, Pope Francis said

“How can I find the wounds of Jesus today? In doing works of mercy–in giving to the body and soul of your brethren, for they are hungry, thirsty, naked, humiliated, slaves, in prison, in hospitals. These are the wounds of Jesus in our day. We must not just touch those wounds: we must heal them.”

The Holy Father spoke like this often, calling the church a field hospital, and urging us to go out and bring the gospel to the wounded. And those wounds can take a lot of forms. People may be suffering physically, or even from their own bad choices. They may be suffering emotionally, barely getting by in this horribly broken world.

They may not be here with us today because too many of them have suffered at the hands of the church, or are scandalized by people who call themselves Christian, but fail to be Christs, myself among them. If we take any lesson from the teaching of Pope Francis, particularly on this Divine Mercy Sunday, let it be that we go out and make Christ present in a wounded world, bringing mercy and healing to our neighbors who may be by the side of the road, just waiting for the shadow of a believer to fall upon them.

In the upcoming weeks the eyes of the entire world will be upon us as the Church chooses a new pope. What we will witness is something that happens only a handful of times in our lives, and it’s filled with meaning and symbolism. The Church is ever ancient, but ever new, with deep roots always putting out living branches.

The world cries out for that right now, when people are so rootless, so dehumanized by technology and separated by politics. All last weekend I kept getting reports from around the world of record-breaking numbers of people coming into the church at the Easter vigil. A hundred in a parish in Texas, hundreds at Notre Dame in Paris, a thousand in Detroit. I heard there were even 5000 in the diocese of Los Angeles. Los Angeles! Which is basically Babylon!

Something is happening, and we need to be there when it happens, ready to tell people: this is why I believe, this is why I feel joy in the presence of the eucharist, this is why I hope. And then we can say to Francis, Rest in peace. We’ll take it from here.

And if you’re interested in the strange, the bizarre, the unexpected side of Church history, try WeirdCatholic.com.

And here’s my friend and fellow Deacon Steve’s homily.

Tom, what a wonderful homily. I've long felt I can relate better to St. Thomas the doubter than to any of the other Apostles. I'm such a "Show me" kind of believer, I probably should have grown up in Missouri rather than New England. But in my case, I'm a Thomas who sincerely wishes he could be more like the beloved disciple John. Alas, I know my mind and heart will harbor some doubt about the veracity of the Gospels until a split second after I croak.

Your thoughts about why we shouldn't fear doubt speak especially deeply to this fellow "Thomas." Congrats on the great homiletics. And thank you for sharing with those of us not lucky enough to be members of your parish. It's a great good to receive your unique witness along with your wise guidance—even if only secondhand :-)

It's funny that you call Los Angeles "Babylon": there's literally a movie made a few years ago about early Hollywood named Babylon! I concur with your statement that it's not fair to label St. Thomas as "the doubter." According to the ending of St. Mark's Gospel, all of the Apostles doubted...twice (Mark 16:9-14). Thank you for your homily.