If there is one terrible disease of our time–particularly among the young–it is despair. Not everyone suffers it, but everyone is touched by it, and it is caused in large part by this unforgiving and cold technocracy we’ve allowed to choke out light and life like weeds in overgrown garden.

We’ve let technology, which can indeed be a blessing and a gift, to insulate us from one another, and particularly from the stranger. That may appear to be an odd claim, since never before have so many “strangers” come into our lives through videos, social media posts, messaging, articles, and, yes, Substacks.

But unless you are one of about two dozen or so people reading this, I am a stranger to you. Truthfully, the real number is three people: my wife and two children. And maybe the dogs.

I only reveal to you what I choose: an image of myself which I have crafted and projected into a bodiless space. It may tally well with what I believe–I certainly hope so, since I’m clergy and a writer of nonfiction–but it is not me. I am something Other. I am someplace else. Were I to describe every inch of the room I’m sitting, every ache and pain I feel, every thing I’m eating and every thought I’m thinking, you would still not arrive at the essence of me, nor would anyone who does the same.

The desperate oversharing we find in so many online spaces is an attempt to be seen, to be heard, to be known by another. I won’t say all this without value. I wouldn’t be here if it was worthless. But I will say that it is insufficient, and yet it has become everything. It’s deadening.

But there is an antidote, and it’s so simple that I’m almost embarrassed to present it as a solution to people who may be suffering in so many ways.

It is, very simply, mercy. And that is everything. It’s a way to beat back the darkness and impersonalism and corrosive discourse that swallows up so much of our mind and heart and time and effort.

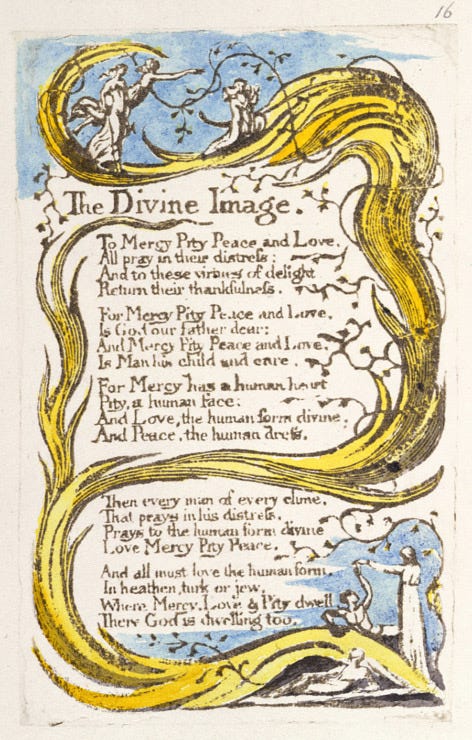

Let’s take that a step further, with a quote from the brilliant madman William Blake, and remember that mercy is found together with three other things:

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

All pray in their distress;

And to these virtues of delight

Return their thankfulness.

It’s who God is, and who he made us to be. Take it in reverse order: we love God and our fellow man because our fellow man is of God, we seek peace and amity with him because he is our brother, we pity him when he is fallen or in need or in dire straits for these reasons, and that love, that, peace, that pity moves us to mercy, which is the hand of God acting in the world.

Blake:

For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

God, that’s beautiful. That’s it. It’s our marching orders, there in the Commandments and the Golden Rule and the Beatitudes and the Gospels and the epistles and beyond, to the great Christian poets and prophets and artists who call us to mercy, pity, peace, and love.

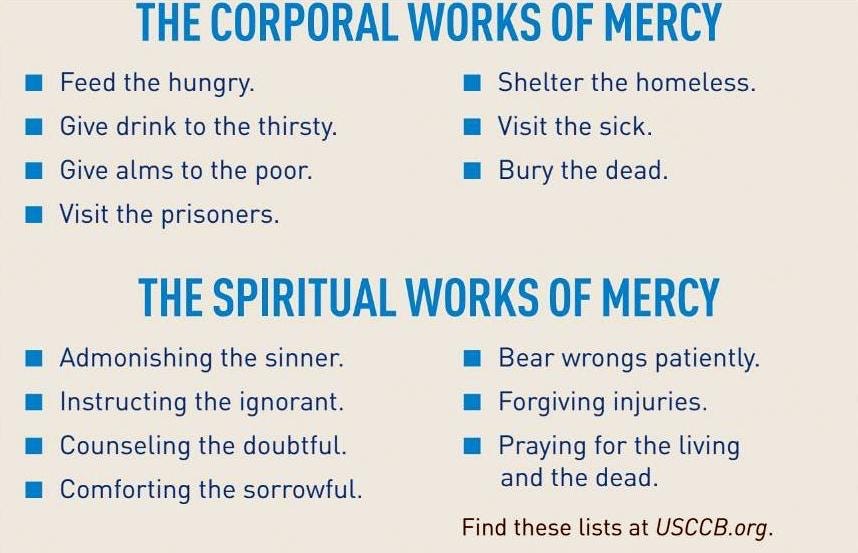

And so the practical antidote is right here, on a little list every child is taught with his catechism, and every adult should consult every morning with a single thought: Which of these will I do today?

We can’t all do all of them, and some days we can barely do one of them. It may be that all our efforts of a day are expended upon bearing wrongs patiently. If so, then we have participated in the work of God, the Opus Dei, that day. We may be the hand extending food from the church pantry or the eucharist at a hospital, or we may be the hand of the hungry person being fed or the patient in the bed, but in any part of the equation, we are participating in the Divine Life.

The spiritual works are always necessary and always in demand, but as we get older we understand that these elemental facts of life are where the rubber meets the road: the sick or hungry child, the difficult old woman, the man whose past has left him on the street or in prison. We can’t pick up every one of them. We can’t solve those problems. But there are problems near to hand, where you are–more than you know. There are children to be taught, and elderly people to be visited, and pantries to be restocked. That’s how the world is healed.

If that’s all I was saying, it would be fairly obvious. But there’s a second part which, I feel, is too often left out, and it is this: It is how you are healed.

We are supposed to be selfless, to give and give and not count the cost. All true. But when we do that, we touch the face of God, and we can never touch God without being healed.

Because God is a fire, it may also wound another part of us. I carry memories from hospital beds that I know will be with me forever. I have experienced supernatural encounters in which I know that was placed in that room at the moment with that person for a reason. I can call to mind, right now, someone and know that I am probably the last person alive who remembers their face, their story. If I was put on earth for no other reason but that moment, it is enough.

Technology is the great insulator: it is a barrier between us and reality. Sometimes–when the house is warm or there is a medicine for the disease–it is a beneficent one. But when we insulate ourselves from each other, we grow numb, we grow lonely, and we fall into despair. And the answer to despair is not joy, although that is a fine thing. The answer to despair is hope–hope received, hope given. And the way to find hope is purpose.

There is a quote from Newman that hangs in my office:

That’s not a call to rush out into the world and start trying to do all things for all people. It is a call to be present to God in each moment, and wonder, What are you calling to me to now, here, in this place, with this person? What man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho will my path cross today? What sick person will I visit, or what doubtful person will I encourage? If the Son of God asks me for a drink of water, will I know his face?

At some moment, on some day, the question will be What cross are you fitting me for today? And in that moment, if we Christians are living as we are commanded to live, there will be no shortage of men from Cyrene to bear it with us.

That’s how we heal the world. That’s how we heal ourselves.

Truly beautiful.

Another banger, Tom. Well done.