In his goodness,

(Jesus) has already counted us as his sons,

and therefore we should never grieve him

by our evil actions.

The Rule of Benedict: Prologue.5

This is part of an occasional series of meditations on the Prologue to the Rule of Benedict.

There’s something unusual in this line from the prologue of the Rule of Benedict. Do you see it?

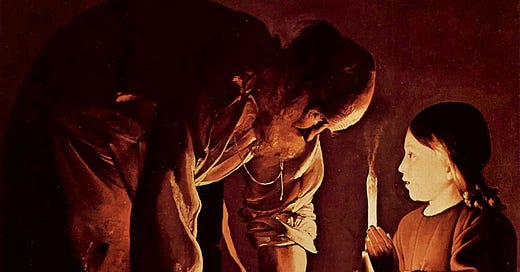

In this passage, Benedict is talking about Jesus as our spiritual father, which became a motif in monastic spirituality. This is not to confuse him with the person of the Father, but to draw out his natural role and the spouse of the church and the spiritual fatherhood he offers to us all.

“In Christ,“ writes the author of Hebrews “I have begotten you.” And one of the particular titles of the messiah in both Isaiah 9:6 is Eternal Father. Jerome calls him “the father of the coming age and of the resurrection, which is completed in our vocation,” while to Eusebius of Caesarea he is the “Father of the coming age of grace.”

It is, then, a spiritual paternity that Christ exercises for the believing Christian, and in his place the Rule assigns earthly spiritual authorities to act in persona Christi. The incarnation gave birth to a new way of being and a new way of relating to God. Jesus himself taught us to call God Father, and offers us a covenant by kinship through baptism. The church understands itself as Christ’s bride, and from this union gives birth to the spiritual life of Christians.

And so, like devoted children, Benedict urges us not to grieve this father by evil actions. In the opposition of values, grief (tristitia) stands opposed to joy (gaudium). God delights in joy when we seek and practice virtue, and sorrows when sin.

As a child, I had a parent who was a yeller. Any grief I caused was met with some level of emotional violence, and it would usually continue for weeks, sometimes months. It never really ended, as the offenses were brought up repeatedly for the rest of my life. The slate was never wiped clean. Maybe something could be forgiven, but it would certainly never be forgotten.

I made a conscious effort to be a different sort of parent, and avoid yelling at all costs. When I asked them about it recently, my kids don’t really remember me yelling at them. What they do remember, however, is a different phrase: I’m very disappointed in you. They never wanted to hear that, and I was careful to use it sparingly.

I’m not trying to act like I’ve found some magic key to parenting. I’m just speaking from my own experience, which gave me some understanding of how we can relate to God the Father and Christ, our spiritual Father. We can relate through abject fear, or through love. We can act in dread of repercussions, or out of the desire not to cause sorrow for one who loves us.

Of course, fear of disappointing is its own kind of fear, and it’s yoked to its own degree of guilt and pain, as my children would also tell you. Indeed, we could call that the true Fear of the Lord which is the beginning of wisdom. Not a trembling, cowardly fear: but a fear of grieving the Father who loves us.

And yet even the chastisement of the Lord is accompanied by delight: “My son, do not despise the Lord’s discipline or be weary of his reproof, / for the Lord reproves him whom he loves, as a father the son in whom he delights.” (Pr 3:11–12) No child wants that delight that every parent has in them children to ever fade. We are born to please. We do not want to grieve those who love us, least of all the One who sees our hearts, and daily calls us back to the path of virtue.

Prayer

Lord, keep the image of your Fatherhood always before us, that we might have the strength to act in a way that will never disappoint you.

Meditation

The family is a school of life, and in it we learn to relate not only to each other, but to God as well. Do we have a damaged image of those relationships that affects how we view God as a parent, and can we find a better way of relating to him as a Father whom we rejoice in pleasing?